Mirror

JOSIF RUNЈANIN (1821–1878) AND OUR TIME

In the Whirlpools of Others

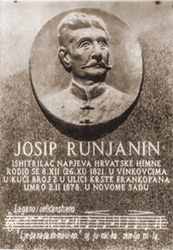

They forcefully classifying him into the Croatian and Yugoslav moulds. And he was born, lived and died as an Orthodox Serb. His family, of soldiers and a priests, originated from Runjani, in Jadar. In the turbulent 18th century, they moved to Semberija, then to Srem and Slavonia. As an Austrian officer, with the foundations of musical education and talent, Josif Runjanin composed many songs to verses known at the time. Two have been preserved. Today, one of them is the Croatian national anthem ”Our Beautiful Homeland”. Last year, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of his birth, his tomb was restored and a memorial service was held at the Uspensko Cemetery in Novi Sad

By: Đorđe M. Srbulović

If he had not composed the song, which will become the Croatian national anthem, and then the national anthem of Croatia, after his death, Josif Runjanin’s history would not have been recorded. In this way, over time, he and his work (one of the two preserved), as well as the tombstones erected to him at Uspensko Cemeteryin Novi Sad, became objects that various people placed in various Yugoslav or Croatian contexts, often overlooking or deliberately keeping silent about the fact that he is an Orthodox Serb and emphasizing some of their own impression or agenda. And there are so many things that it are not easy to write about Runjanin: on the one hand – his life does not have any unusual events, and on the other – so many events were intertwined around him, even in the times when he was no longer alive. So I will try, within the limits of my power and knowledge, to tell the story of Josif Runjanin, about some posthumous appropriations and placements where he did not belong during his life, about ”Our Beautiful Homeland” and its roads, and about the tombstone, and the fates of some people in some ways associated with him.

If he had not composed the song, which will become the Croatian national anthem, and then the national anthem of Croatia, after his death, Josif Runjanin’s history would not have been recorded. In this way, over time, he and his work (one of the two preserved), as well as the tombstones erected to him at Uspensko Cemeteryin Novi Sad, became objects that various people placed in various Yugoslav or Croatian contexts, often overlooking or deliberately keeping silent about the fact that he is an Orthodox Serb and emphasizing some of their own impression or agenda. And there are so many things that it are not easy to write about Runjanin: on the one hand – his life does not have any unusual events, and on the other – so many events were intertwined around him, even in the times when he was no longer alive. So I will try, within the limits of my power and knowledge, to tell the story of Josif Runjanin, about some posthumous appropriations and placements where he did not belong during his life, about ”Our Beautiful Homeland” and its roads, and about the tombstone, and the fates of some people in some ways associated with him.

Facts are not so easy to come by. Thus, for example, Serbian-Yugoslavian encyclopedias, including Stanojević’s National Serbo–Croatian–Slovenian Encyclopedia from 1929, as well as the Small Encyclopedia Prosveta from 1969, christen him and write his name as Josip, whereby each classifies him in its own Yugoslav framework – monarchical or socialist–republican. I did not search through Croatian literature: a brief look at the Croatian Encyclopedia available on the Internet, where he is also listed as Josip, shows that I was right. There are also completely unfounded assumptions, so dealing with it is a complete waste of time.

JOSIF AND AROUND HIM

Most of the quality information about Runjanin is given in a small article by Ilija Vrsajkov – today a forgotten personality of the Novi Sad music scene – first of all. The publication Josif Runjanin was published in Novi Sad (”Nevkoš”, 2000). In it, we learn that, according to tradition, the ancestors of Josif Runjanin left the area around Shkodra during the time of King Dragutin and founded the Runjani settlement near Loznica, as it is still called today. The first written trace of this family comes from the pen of Josif’s grandfather Petar (1775–1835), who in his Autobiography (edited and published in Bogoslovski vesnik in Sremski Karlovci by Dr. Nikola Radojčić in 1914) states that his ancestors always helped Austria against Turks, so after 1716, they had to take refuge in Belino (today’s Bijeljina), and after the Peace of Belgrade in 1739, they crossed the Sava and settled in the then Habsburg Monarchy. One part of the family went to Osek, and the other – from which Josif would descend, settled in Srem, in the town of Grk, and then in Kuzmin, where Petar would become a priest and would bear the nickname Kuzminčani after him. Josif also bore this nickname, as evidenced in the 24th volume of the Encyclopedia of Novi Sad by Dr. Magdalena Veselinović Šulc and Milorad Botić (Novi Sad, Novosadski klub, 2004). Petar left behind several works, but the aforementioned is the most famous.

Most of the quality information about Runjanin is given in a small article by Ilija Vrsajkov – today a forgotten personality of the Novi Sad music scene – first of all. The publication Josif Runjanin was published in Novi Sad (”Nevkoš”, 2000). In it, we learn that, according to tradition, the ancestors of Josif Runjanin left the area around Shkodra during the time of King Dragutin and founded the Runjani settlement near Loznica, as it is still called today. The first written trace of this family comes from the pen of Josif’s grandfather Petar (1775–1835), who in his Autobiography (edited and published in Bogoslovski vesnik in Sremski Karlovci by Dr. Nikola Radojčić in 1914) states that his ancestors always helped Austria against Turks, so after 1716, they had to take refuge in Belino (today’s Bijeljina), and after the Peace of Belgrade in 1739, they crossed the Sava and settled in the then Habsburg Monarchy. One part of the family went to Osek, and the other – from which Josif would descend, settled in Srem, in the town of Grk, and then in Kuzmin, where Petar would become a priest and would bear the nickname Kuzminčani after him. Josif also bore this nickname, as evidenced in the 24th volume of the Encyclopedia of Novi Sad by Dr. Magdalena Veselinović Šulc and Milorad Botić (Novi Sad, Novosadski klub, 2004). Petar left behind several works, but the aforementioned is the most famous.

Josif was born to Peter’s eldest son, Ignjat (1798–1846), a construction captain from Krajina, and his wife Sofia, on 26 November, according to the Julian calendar, or 8 December 1821, according to the Gregorian calendar. He was the eldest of seven children. He was baptized in the Orthodox church in Vinkovci, which according to Milivoj Pavlović (The Anthem Book – Yugoslav Nations in the Anthem and the Anthem Among the Nations, Gornji Milanovac, ”Dečije novine”, Third Revised and Updated Edition, 1990), there is evidence in the books of the Serbian church there. He finished elementary school and high school in his native Vinkovci. Pavlović states that he graduated from the Cadet School after high school, and that he was a cadet corporal in the Glina regiment from 1840, while Vrsajkov that he was recruited as an ordinary soldier on 25 December 1835. Only then, both of them ”brought” him to the Ogulin Military Regiment, to the First Ban Regiment, which was then commanded by Colonel Josip Jelačić. According to the research conducted and published by Vrsajkov, Runjanin was musically gifted, had a ringing tenor, played the guitar, zither and piano, he was accepted by the military chaplain, Josip Vendl, who taught him sheet music and directed him to opera music. But I will say something about that later. As for his further military and private life, he moved in the following direction: he remained in Glina until 1848, when he went to the Italian front, promoted to the rank of lieutenant. He stood out for his bravery in battles, and in the same year he became a first lieutenant, and the following year a captain of the second class. It took eight years to reach the rank of captain of the first class... He will be on the battlefield on two more occasions: in 1859 and 1866, when he was promoted to the rank of major. In 1864, he married Otilia, the daughter of retired captain Toma Peraković. In 1868, their daughter Wilhelmina was born. It is interesting that in the Book of the Dead of the Church of the Assumption (No. IV for 1876–1882, on p. 85, where information about the death and funeral of Josif Runjanin is entered, his religion is written as Orthodox, and his wife’s as Roman Catholic). He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1871, and transferred to the Mecklenburg–Strelitz, and then to the Wenzl regiment.

Josif was born to Peter’s eldest son, Ignjat (1798–1846), a construction captain from Krajina, and his wife Sofia, on 26 November, according to the Julian calendar, or 8 December 1821, according to the Gregorian calendar. He was the eldest of seven children. He was baptized in the Orthodox church in Vinkovci, which according to Milivoj Pavlović (The Anthem Book – Yugoslav Nations in the Anthem and the Anthem Among the Nations, Gornji Milanovac, ”Dečije novine”, Third Revised and Updated Edition, 1990), there is evidence in the books of the Serbian church there. He finished elementary school and high school in his native Vinkovci. Pavlović states that he graduated from the Cadet School after high school, and that he was a cadet corporal in the Glina regiment from 1840, while Vrsajkov that he was recruited as an ordinary soldier on 25 December 1835. Only then, both of them ”brought” him to the Ogulin Military Regiment, to the First Ban Regiment, which was then commanded by Colonel Josip Jelačić. According to the research conducted and published by Vrsajkov, Runjanin was musically gifted, had a ringing tenor, played the guitar, zither and piano, he was accepted by the military chaplain, Josip Vendl, who taught him sheet music and directed him to opera music. But I will say something about that later. As for his further military and private life, he moved in the following direction: he remained in Glina until 1848, when he went to the Italian front, promoted to the rank of lieutenant. He stood out for his bravery in battles, and in the same year he became a first lieutenant, and the following year a captain of the second class. It took eight years to reach the rank of captain of the first class... He will be on the battlefield on two more occasions: in 1859 and 1866, when he was promoted to the rank of major. In 1864, he married Otilia, the daughter of retired captain Toma Peraković. In 1868, their daughter Wilhelmina was born. It is interesting that in the Book of the Dead of the Church of the Assumption (No. IV for 1876–1882, on p. 85, where information about the death and funeral of Josif Runjanin is entered, his religion is written as Orthodox, and his wife’s as Roman Catholic). He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1871, and transferred to the Mecklenburg–Strelitz, and then to the Wenzl regiment.

Already in 1876, he retired. He was forced to. Namely, as noted by Vrsajkov, during an official trip to Vienna, Runjanin had to spend the night in a roadside inn. While he was having dinner, a drunk hussar came to his table, took a candle from the table, lit a cigarette and put out the candle. Runjanin challenged him to a duel and ripped open his stomach. Officers had the right to duel, but had to get permission from higher authorities first. Joseph did not have that approval. As the duel without permission was his second such case, and the first time they cut him some slack, and as the hussar was also a Hungarian nobleman, this time there was no forgiveness and he was retired. He settled in Novi Sad, which was almost a common practice of retired Serbian officers, and Vasa Stajić called Novi Sad ”penziopolis” because of that. According to Vrsajkov, his wife and daughter did not come with him, because they were most likely already divorced then (1871 is mentioned as the year of separation). Otilia went with her daughter to her parents in Graz, where she would soon die, so the child was raised by her grandparents. Wilhelmina would be remembered by everyone on the centenary of Runjanin’s birth, in 1921, Croats and Serbs will send her some money, because she lived there in poverty and disease, and then she would fall into oblivion. It is not known when she died or where her grave is. Runjanin settled in Lenau Street (house no. 953), later Cetinjska Street, then named after him, then demolished and non–existent. Two years later, he dies of a stroke – apoplexy – as stated in the Book of the Dead of the Church of the Assumption. The date of his death was given as 8 January 1878, and his funeral on 10 January. In the religion section, Eastern Orthodox was entered, the deceased was confessed and received communion, and according to the information from the Book of the Dead, as a note, albeit crossed out, it was stated that the wife and daughter live ”privately in the city”. What kind of relationships they had and whether they were in a relationship – remains a secret, but – like everything else, no historical ”spectacle” exists in his life. According to some researchers of Novi Sad’s past, he died in poverty, and none of his relatives were present at the funeral. Later, much later after his death, when ”Our Beautiful Homeland” became the Croatian national anthem, but also part of the national anthem in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians/Yugoslavia, there will be, and still are, Croatian researchers who will claim that Runjanin is a Croat. ”If someone doesn’t know that Josif Runjanin is an Orthodox Serb, that shows that he is not really interested in Runjanin’s past” – said Vasa Stajić, one of the best experts on of Novi Sad’s past, adding that such assertions are nonsense.

Already in 1876, he retired. He was forced to. Namely, as noted by Vrsajkov, during an official trip to Vienna, Runjanin had to spend the night in a roadside inn. While he was having dinner, a drunk hussar came to his table, took a candle from the table, lit a cigarette and put out the candle. Runjanin challenged him to a duel and ripped open his stomach. Officers had the right to duel, but had to get permission from higher authorities first. Joseph did not have that approval. As the duel without permission was his second such case, and the first time they cut him some slack, and as the hussar was also a Hungarian nobleman, this time there was no forgiveness and he was retired. He settled in Novi Sad, which was almost a common practice of retired Serbian officers, and Vasa Stajić called Novi Sad ”penziopolis” because of that. According to Vrsajkov, his wife and daughter did not come with him, because they were most likely already divorced then (1871 is mentioned as the year of separation). Otilia went with her daughter to her parents in Graz, where she would soon die, so the child was raised by her grandparents. Wilhelmina would be remembered by everyone on the centenary of Runjanin’s birth, in 1921, Croats and Serbs will send her some money, because she lived there in poverty and disease, and then she would fall into oblivion. It is not known when she died or where her grave is. Runjanin settled in Lenau Street (house no. 953), later Cetinjska Street, then named after him, then demolished and non–existent. Two years later, he dies of a stroke – apoplexy – as stated in the Book of the Dead of the Church of the Assumption. The date of his death was given as 8 January 1878, and his funeral on 10 January. In the religion section, Eastern Orthodox was entered, the deceased was confessed and received communion, and according to the information from the Book of the Dead, as a note, albeit crossed out, it was stated that the wife and daughter live ”privately in the city”. What kind of relationships they had and whether they were in a relationship – remains a secret, but – like everything else, no historical ”spectacle” exists in his life. According to some researchers of Novi Sad’s past, he died in poverty, and none of his relatives were present at the funeral. Later, much later after his death, when ”Our Beautiful Homeland” became the Croatian national anthem, but also part of the national anthem in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians/Yugoslavia, there will be, and still are, Croatian researchers who will claim that Runjanin is a Croat. ”If someone doesn’t know that Josif Runjanin is an Orthodox Serb, that shows that he is not really interested in Runjanin’s past” – said Vasa Stajić, one of the best experts on of Novi Sad’s past, adding that such assertions are nonsense.

OUR BEAUTIFUL HOMELAND AND AROUND IT

Although, according to the testimony of Josif’s cousin, Dr. Nikola Runjanin (Kuzmin, 1835 – Ruma, 1898), Josif composed many songs even when he was on leave in Vinkovci, when he (Nikola) would come to see him with other children, Josif played and sang them, only two songs from his entire opus have been preserved. He was very cheerful, loved to joke and that’s why everyone loved him. His ”musical activity” takes us back to the time of his service in Glina. As there were a lot of nationally inspired people at that time, among them Ivan Trnski and Petar Preradović, and as the ideas of the (banned) Illyrian movement dominated among Serbs and Croats, young Austrian officers, so Runjanin’s musical talent and ideas expressed Illyrianism through his songs. Trnski wrote lyrics for Colonel Jelačić, ”We love you, our pride”, and Runjanin, in 1843, composed the music, taking as a basis the significantly reworked beginning of Donizetti’s opera The Elixir of Love (Pavlović says according to an Italian melody). Due to its melodiousness, this song was soon sung by all the regiments. Runjanin’s original has not been preserved, but the one that was recorded half a century later according to the regimental song.

Although, according to the testimony of Josif’s cousin, Dr. Nikola Runjanin (Kuzmin, 1835 – Ruma, 1898), Josif composed many songs even when he was on leave in Vinkovci, when he (Nikola) would come to see him with other children, Josif played and sang them, only two songs from his entire opus have been preserved. He was very cheerful, loved to joke and that’s why everyone loved him. His ”musical activity” takes us back to the time of his service in Glina. As there were a lot of nationally inspired people at that time, among them Ivan Trnski and Petar Preradović, and as the ideas of the (banned) Illyrian movement dominated among Serbs and Croats, young Austrian officers, so Runjanin’s musical talent and ideas expressed Illyrianism through his songs. Trnski wrote lyrics for Colonel Jelačić, ”We love you, our pride”, and Runjanin, in 1843, composed the music, taking as a basis the significantly reworked beginning of Donizetti’s opera The Elixir of Love (Pavlović says according to an Italian melody). Due to its melodiousness, this song was soon sung by all the regiments. Runjanin’s original has not been preserved, but the one that was recorded half a century later according to the regimental song.

All this would have been recorded only as a Croatian patriotic song from the mid-19th century, if it had not been for the composition of the song based on the lyrics of Antun Mihanović ”Croatian Homeland”. That song lives its life today as the anthem of the Republic of Croatia ”Our Beautiful Homeland”. Runjanin composed music to these verses in 1846. The poem was published in the newspaper of Ljudevit Gaj, Danicza Horvatzka, Slavonzka y Dalmatinzka, no. 10, on the front page, on 10 March 1835. For some reason, its author, Antun Mihanović, signs it as Mi......ć. If it had not been for Runjanin and his melody, the poem would probably have been forgotten.

Once, in response to this remark about being forgotten, Matoš said that the song cannot be imagined without music and singing! Mihanović’s verses will be published in various newspapers throughout the South Slavic world, including in the Principality of Serbia. But the following is important: When Mihanović wrote this poem, Runjanin was 14 years old and attended high school in his native Vinkovci. When he composed and performed the song, 14 years later, Mihanović was far away, probably already in the USA. The two have almost certainly never met. According to Pavlović, when composing ”Our Beautiful Homeland”, Runjanin relied a lot on Donizetti’s melody from the opera Lucia di Lammermoor, more precisely on the duet of Edgar and Enrico from the first scene of the third act (meeting of the opponents in the old tower). In modern performances of Lucia di Lammermoor, this melody is not present, it was long ago rejected as anachronistic and extremely clumsily performed. Runjanin did it better. In the same year that it was composed, Runjanin’s composition reached Zagreb, through folk singing. It was immediately accepted by the masses.

Once, in response to this remark about being forgotten, Matoš said that the song cannot be imagined without music and singing! Mihanović’s verses will be published in various newspapers throughout the South Slavic world, including in the Principality of Serbia. But the following is important: When Mihanović wrote this poem, Runjanin was 14 years old and attended high school in his native Vinkovci. When he composed and performed the song, 14 years later, Mihanović was far away, probably already in the USA. The two have almost certainly never met. According to Pavlović, when composing ”Our Beautiful Homeland”, Runjanin relied a lot on Donizetti’s melody from the opera Lucia di Lammermoor, more precisely on the duet of Edgar and Enrico from the first scene of the third act (meeting of the opponents in the old tower). In modern performances of Lucia di Lammermoor, this melody is not present, it was long ago rejected as anachronistic and extremely clumsily performed. Runjanin did it better. In the same year that it was composed, Runjanin’s composition reached Zagreb, through folk singing. It was immediately accepted by the masses.

Where and how was the song that would later become the Croatian national anthem performed for the first time? According to the most likely version, it was performed for the first time in Glina, in the house of Serbian merchant Petar Peleš. Zagreb’s Jutarnji list from 1939 announced that there is still a piano in Glina on which Runjanin performed this composition for the first time. According to some reports, he played (and sang) it on the guitar. Versatile and musically literate and educated, he played several instruments. The Novi Sad newspaper Branik from 04 September 1910 quotes the words of Petar Peleš himself, who says that ”we, in the Serbian Charitable Singing Society in Glina, were the first to sing the Croatian national anthem in 1846. The first tenor was sung by Jovan (Josif) Runjanin, the second tenor the merchant Petar Peleš, the cadet Nikola Mirić and the customs officer Jovan Rakić; first bass lieutenant Kuzman Drakulić, second bass teacher Jovan Novaković and bandleader Dragutin Salauka.” There are volumes of writings and books about the Croatian national anthem, so we will not delve deeper into that story. It should only be said that over time the song not only retained, but also increased its  popularity and became more and more accepted, that it experienced a really large number of arrangements (including both church and Slovenian), that today’s version is slightly different from Runjanin’s. During August and September 1891, a large economic (fair) exhibition was held in Zagreb. On that occasion, a choir performance and selection for the Croatian national anthem was held. Among the multitude of songs by famous authors, among the multitude of also popular and accepted patriotic and national songs, ”Our Beautiful Homeland” had no competition and was unanimously chosen by the expert jury and enthusiastic audience, and was performed hundreds of times during the exhibition. For the first time, a part of the song will become part of the national anthem (until then it was only the national anthem) in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians/Yugoslavia (along with parts of the Serbian national and Slovenian national anthems). Whether Stanislav Binički, or a Serbian volunteer at the front, the Croat Anto Kovač, arranged this ”combination” into one hymn in 1917 (this is more likely), remains to be fully investigated. Kovač died in Belgrade in 1972. The Croatian national anthem became the national anthem for the first time during the NDH, and Pavelić himself changed Mihanović’s lyrics, adapting them to his own intelligence. The song was allegedly also sung by Croatian partisans. In the second Yugoslavia, ”Our Beautiful Homeland” officially appeared for the first time as a scandal: at the table tennis match between Yugoslavia and Japan in 1970, in Zagreb, this song was played instead of the national anthem ”Hey, Slavs”, and then, at the airport in Zagreb, on 06 September 1971, during the reception of President Tito, this song was played, again instead of the anthem song. With the Constitution of the SR Croatia from 1974, the issue of this song was resolved and it was the only republican anthem in the former state, and its status was regulated by the constitution (somewhere it is said that its status was regulated by constitutional amendments, 1971). Today it is the official anthem of the Republic of Croatia.

popularity and became more and more accepted, that it experienced a really large number of arrangements (including both church and Slovenian), that today’s version is slightly different from Runjanin’s. During August and September 1891, a large economic (fair) exhibition was held in Zagreb. On that occasion, a choir performance and selection for the Croatian national anthem was held. Among the multitude of songs by famous authors, among the multitude of also popular and accepted patriotic and national songs, ”Our Beautiful Homeland” had no competition and was unanimously chosen by the expert jury and enthusiastic audience, and was performed hundreds of times during the exhibition. For the first time, a part of the song will become part of the national anthem (until then it was only the national anthem) in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians/Yugoslavia (along with parts of the Serbian national and Slovenian national anthems). Whether Stanislav Binički, or a Serbian volunteer at the front, the Croat Anto Kovač, arranged this ”combination” into one hymn in 1917 (this is more likely), remains to be fully investigated. Kovač died in Belgrade in 1972. The Croatian national anthem became the national anthem for the first time during the NDH, and Pavelić himself changed Mihanović’s lyrics, adapting them to his own intelligence. The song was allegedly also sung by Croatian partisans. In the second Yugoslavia, ”Our Beautiful Homeland” officially appeared for the first time as a scandal: at the table tennis match between Yugoslavia and Japan in 1970, in Zagreb, this song was played instead of the national anthem ”Hey, Slavs”, and then, at the airport in Zagreb, on 06 September 1971, during the reception of President Tito, this song was played, again instead of the anthem song. With the Constitution of the SR Croatia from 1974, the issue of this song was resolved and it was the only republican anthem in the former state, and its status was regulated by the constitution (somewhere it is said that its status was regulated by constitutional amendments, 1971). Today it is the official anthem of the Republic of Croatia.

THE GRAVE AND AROUND IT

Events surrounding the grave and tombstone of Josif Runjanin will begin in 1921, on the centenary of his birth. Before that, at the end of the 19th century, Ilija Ognjanović Abukazem – a chronicler of Novi Sad in his time, recorded in the booklet Graves of Famous Serbs Whose Bones Were Buried in Novi Sad, basic information about Runjanin as well: ”father Ignjat, mother Sofija, godmother at the baptism Sultana Mihaljević, etc. He was buried at the Uspensko Cemetery in Novi Sad on 10 January 1878. His grave is on the left side of the main road... There are no monuments on his grave, but a small oak cross, which is buried in the forehead of the head, with an inscription’Josif Runjanin C. Kr. lieutenant colonel’ has been preserved very well to this day.”

Events surrounding the grave and tombstone of Josif Runjanin will begin in 1921, on the centenary of his birth. Before that, at the end of the 19th century, Ilija Ognjanović Abukazem – a chronicler of Novi Sad in his time, recorded in the booklet Graves of Famous Serbs Whose Bones Were Buried in Novi Sad, basic information about Runjanin as well: ”father Ignjat, mother Sofija, godmother at the baptism Sultana Mihaljević, etc. He was buried at the Uspensko Cemetery in Novi Sad on 10 January 1878. His grave is on the left side of the main road... There are no monuments on his grave, but a small oak cross, which is buried in the forehead of the head, with an inscription’Josif Runjanin C. Kr. lieutenant colonel’ has been preserved very well to this day.”

In fact, the events, of which Runjanin will only be the occasion and the object, begin on the centenary of his birth, and a little more than four decades after his death, in 1921, and are still going on. They were started by Croats by emphasizing their separate identity, national and state differences in relation to the Serbs, by placing a memorial plaque to the composer of ”Our Beautiful Homeland” at the birthplace in Vinkovci and organizing large events in his honor. Of course, he was also written here as Josip, because at that time the stories about Runjanin’s Croatian ethnicity were already in full swing, and there were efforts to transfer his remains to Croatia. (On the centenary of the publication of Mihanović’s verses, in 1935, the Croats will erect a monument to their national anthem near Kumrovac.) The Serbs, again, insist on Runjanin’s ”proto–Yugoslavism”. That everything has no direct connection with Runjanin is also evidenced by the fact that no one was interested in his wife (who had since died) and his sick and poor daughter, except that both Croats and Yugoslavs sent the daughters some money to Graz for her father’s centenary, but the date and place of her funeral are unknown.

As the cross on the grave, which we mentioned quoting Abukazem, rotted and had to be replaced (even the replaced one did not have better fate), so in 1921, an action was started in Novi Sad to decorate the grave and erect a tombstone for Josif Runjanin. The Novi Sad daily newspaper Zastava writes about this, noting that there is no grave marker, that the deceased died in misery and poverty, that not even his closest relatives saw him off, etc. Although there are no documents on this topic in the Novi Sad archive and the only thing we have are a few texts in the mentioned diary, the impression remains that the top of the state was behind this action, in a somewhat obscure way, and the action itself was supposed to promote a new state and unity of ”one people with three names”. A committee for erecting a monument was formed, which included: priest Veljko Mirosavljević, chairman of the Committee, originator of the idea of erecting a monument; Greek Catholic priest Jovan Hranilović, otherwise the first chairman of the Great National Assembly, in 1918, as vice–chairman; and Franjo Malin, a Croat, former Catholic priest in Istria, later Old Catholic in Petrovaradin, as secretary. Through the newspaper, the committee invited everyone to help erect a worthy monument, printed commemorative postcards with Runjanin’s image and in other ways tried to popularize its activity and collect as much funds as possible. People responded, and according to committee  members, there were also individuals who promised to finance the monument themselves – if not enough funds were collected. According to the Chairman of the Board, more than 26,000 dinars were collected in the next three years. The draft of the monument was made by the court architect Gojko Todić, and the bronze bas–relief on the monument was made by Đorđe Jovanović, a famous sculptor and later academician. However... In the monograph about this sculptor, authored by Miodrag Jovanović (Novi Sad, Matica srpska Gallery, 2005), there is no mention of this bas–relief. During the restoration, in 2021, when the bas–relief was thoroughly cleaned, a signature was observed above Josif Runjanin’s right shoulder: ”Milorad Jovanović 1937”. We are talking about a lesser–known sculptor from Sremska Mitrovica (1889–1946), who made a number of bas–reliefs for tombstones, and is also known for his collaboration with Gojko Todić. However, the Novi Sad Zastava, reporting from the ceremonial unveiling and consecration of the monument, which took place on St. Peter’s Day in 1924, reported that the bas–relief of Đoka Jovanović, although with a slight delay, finally arrived and was placed on the composer’s grave. When the bas–relief was replaced and why – I have not been able to determine. During the last renovation, the missing panel was returned to the background of the monument, as well as the large trefoil cross on the tombstone, but it was also noticed that the first four beats of the hymn, which are carved in the upper part of the monument, were changed. Namely, Runjanin’s opening beats are slightly different from the current opening beats of ”Our Beautiful Homeland”. It was left as someone modified it (probably carving the current version). When and who made these changes – I have not been able to find, I guess after the Second World War, when a different Yugoslavism compared to the one after the First World War was promoted.

members, there were also individuals who promised to finance the monument themselves – if not enough funds were collected. According to the Chairman of the Board, more than 26,000 dinars were collected in the next three years. The draft of the monument was made by the court architect Gojko Todić, and the bronze bas–relief on the monument was made by Đorđe Jovanović, a famous sculptor and later academician. However... In the monograph about this sculptor, authored by Miodrag Jovanović (Novi Sad, Matica srpska Gallery, 2005), there is no mention of this bas–relief. During the restoration, in 2021, when the bas–relief was thoroughly cleaned, a signature was observed above Josif Runjanin’s right shoulder: ”Milorad Jovanović 1937”. We are talking about a lesser–known sculptor from Sremska Mitrovica (1889–1946), who made a number of bas–reliefs for tombstones, and is also known for his collaboration with Gojko Todić. However, the Novi Sad Zastava, reporting from the ceremonial unveiling and consecration of the monument, which took place on St. Peter’s Day in 1924, reported that the bas–relief of Đoka Jovanović, although with a slight delay, finally arrived and was placed on the composer’s grave. When the bas–relief was replaced and why – I have not been able to determine. During the last renovation, the missing panel was returned to the background of the monument, as well as the large trefoil cross on the tombstone, but it was also noticed that the first four beats of the hymn, which are carved in the upper part of the monument, were changed. Namely, Runjanin’s opening beats are slightly different from the current opening beats of ”Our Beautiful Homeland”. It was left as someone modified it (probably carving the current version). When and who made these changes – I have not been able to find, I guess after the Second World War, when a different Yugoslavism compared to the one after the First World War was promoted.

The consecration and unveiling of the monument was a great ceremony, held on Saturday, St. Peter’s Day (July 12) in 1924. Hundreds of people attended, among them the participants of the Congress of Yugoslav Architects and Engineers, which began its work in Novi Sad that very day, the city leaders with Mayor Stefanović, the Bishop of Bačka Dr. Irinej with all the priests of Novi Sad, and the following choirs and singing societies sang: Music, Petrovaradin ”Neven”, Hungarian–reformation, German ”Jugend-Choir”, Jewish ”Hezamer”, all under the direction of Svetolik Pašćan. Everyone sang ”Our Beautiful Homeland”, and according to the newspaper, it was especially touching when they broke the cake over the grave: Bishop of Bačka, Franjo Malin and Eng. Janko Mačkovšek. On the plaque on the back of the monument, among other things, it was written: ”This monument was erected by Serbs and Croats on 12 July 1924...” The text is written in both Cyrillic and Latin letters, and Serbian and Croatian spelling.

On the same day, at the house where he spent his last years and died, a ”tasteful” memorial plaque was placed, which read: ”He lived and died in this house on 8/20. 1878. Josif Runjanin, the composer of ”Our Beautiful Homeland””. The house was demolished at the end of the last century, and the plaque disappeared earlier. The street no longer exists either.

***

Mihanović

Antun Mihanović (1796–1861) is an important person of Croatian culture, science and politics. For this occasion, we will give only a few data that connect him to Serbia. First of all, it should be said that he was older than the ”Illyrians”, so in a way he is considered their forerunner, because he advocated for the national language. In Vienna, he socialized with Vuk and Kopitar and shared their views on language and writing. Austria appointed him as an ambassador to the Principality of Serbia and he was the first ambassador to come to the restored Serbian state (1836–1838). Although he believed that he was ”among his South Slavic brothers”, Miloš was not at all happy about this arrival, because he believed that the foreigners would control him more through the deputies and that he would not be able to rule ”at his will”. In Belgrade, Mihanović fell in love with Jevrem Obrenović’s daughter – Anka, and she with him – even though she was much younger. The marriage did not take place, because the Obrenovićs objected. He will later go to Thessaloniki, then to Mount Athos, then... all the way to the USA. Anka married Aleksandar Konstantinović, and she will die together with her brother, Prince Mihailo, in the assassination in Košutnjak in 1868. Mihailo was in love with Anka’s daughter – Katarina (his cousin) and wanted to marry her.

***

Todić

Architect Gojko Todić (father Vaso, mother Anita) was born on 12 August 1896, in Gradiška. He was married to Radmila (1900), and had a daughter Olga (1924). He finished high school in Banja Luka, where he was arrested as a student for membership in the banned organization ”Yugoslavia”. After the formation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians, he went to Belgrade to study architecture. He designed villas all over Belgrade for a wealthy clientele, and King Aleksandar himself became interested in his work. He designed, among other things: a radio station in Belgrade, a building in Nemanjina no. 9, the railway station in Sremska Mitrovica, the hotel and bathhouse ”Šumadija” in Arandjelovac, the Sharia Gymnasium in Sarajevo, the reconstruction of the National Theater in Belgrade, together with Ilkić completed the building of the National Assembly, the memorial to the soldiers who died at Gučevo in 1914, the AOB reservoir building (astronomical observation), participated in the design of the Patriarchate building in Belgrade, parts of the Palace, etc., etc. He acquired a large capital. According to some data, he invested the money in the purchase of real estate, mainly in Belgrade. It probably cost him his life. Although his death has not been confirmed, because according to rare and less probable information, he took refuge in Argentina before the end of the war and died there, most likely he was shot with his wife and daughter immediately after the liberation of Belgrade, in the fall of 1944, and all his property was confiscated. I hope that someone will thoroughly and professionally investigate the life and work of this man and return him to Serbian culture and history. I would like to thank my colleagues from the Faculty of Architecture, the Museum of Science and Technology and the Institute for Contemporary History in Belgrade, as well as architectural historians and architects from Novi Sad, for the information provided.